Philosophy of Librarianship

I am a member of a three-librarian team collaboratively overseeing our libraries’ web services. My concentration is on user experience— encompassing areas such as information architecture, content management, usability testing, and web accessibility. I also manage our frontline services such as our LibGuides publishing system and LibCal online reservation system. When our team’s work is at its best, you stop noticing it — it just works. Just as you’ve internalized driving a car, our library systems should be just as natural. The joy, or frustration, should come from your research, and not from our tools.

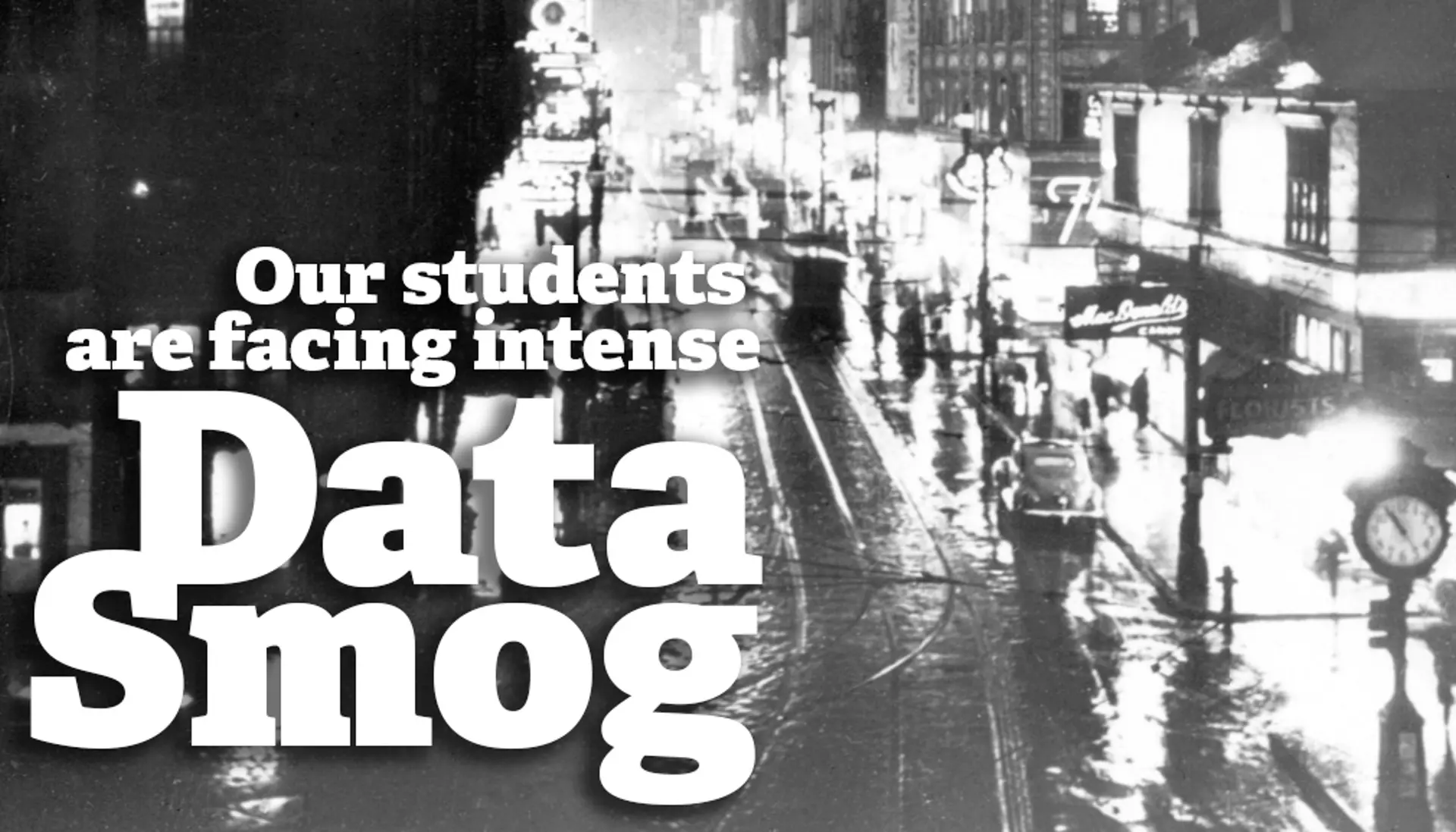

I believe this experience is critical, because the research required for our students’ educational journey is paradoxically both far easier and more difficult than ever before. For instance, doing a search for “education” through our libraries’ website takes just seconds, but returns 25 million results. Research material is more readily available than at any time in history and our students are absolutely overwhelmed with information. Journalist David Shenk coined this paradox “data smog.” Our students’ reaction to this data smog ranges from sheer panic to blind acceptance. This results in our students frequently grabbing the first remotely appropriate source they find.

I’ve witnessed this behavior firsthand in multiple environments — both having worked with students at the reference desk in my previous positions and in working with my own students teaching a 3-credit course on interaction design here at Miami. Our students’ reaction, which is an indictment of our information environment, is one I take personally and I know I can be part of the solution. I do so by working continually to make our libraries’ online services as clear and useful as possible. It starts with a multi-pronged process of learning— I am continually listening to our librarians who work with our students (both at my home institution and nationally via my service), I teach a 3-credit class and learn about my students and their needs first-hand, I volunteer for library and university activities that allow me to interact with our students on a regular basis, I collaborate with my colleagues on usability testing of our services and research tools, and finally I collaborate on original research to learn what research experience first-year students bring with them from high school to college. All this cumulative learning, testing, and research allows me to participate in the process of continually improving the usability of our online services. In the end, I hope these efforts will allow our students to see clarity instead of data smog while conducting their research.

Illustration

The photograph of downtown Pittsburgh c.1940 appears to be late night, but is actually 10:55 in the morning. Every light in the city is one due to heavy smog from the city’s steel mills. This is a photo from a series of images taken to document the city of Pittsburgh before and after smoke control ordinances were passed regulating the burning of coal.

Citations

Shenk, D. (1997, May). Data smog. MIT’s Technology Review. p. 18.

“Corner of Liberty and Fifth Avenues 10:55 AM.” (c.1940) Smoke Control Lantern Slide Collection, Historic Pittsburgh hosted by the University of Pittsburgh Library System.